The Pelagian heresy is the idea that human beings are ultimately good at the core and have the ability to choose between good and evil due to their free will.

(Heresy: “opinion or doctrine at variance with the orthodox or accepted doctrine, especially of a church or religious system.”)

The Pelagian heresy (or Pelagianism) directly contradicts the doctrine of original sin which both the Old and New Testaments affirm.

Romans 3:10 can’t be more clear: “There is none righteous, not even one.” Jeremiah goes on: “The heart is more deceitful than all else and is desperately sick; Who can understand it?” (Jeremiah 17:9) Isaiah continues: “All our righteous deeds are like a filthy garment.” (Isaiah 64:6b) Jesus adds: “No one is good except God alone.” (Mark 10:18b)

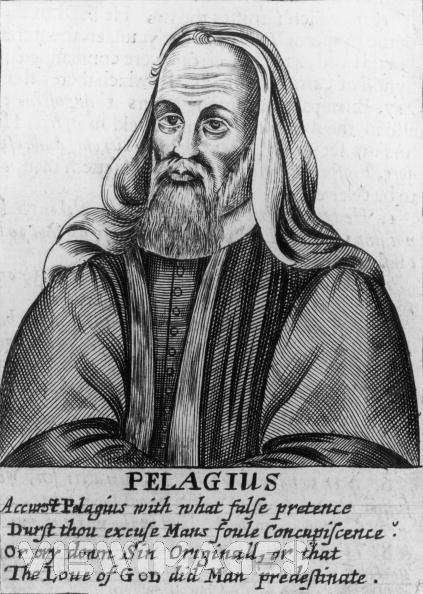

The Pelagian heresy first appeared in the 5th century as taught by Pelagius and was opposed by Augustine of Hippo.

SEMI-PELAGIANISM

It is important to note here another form of the Pelagian heresy that arose afterwards referred to as semi-Pelagianism.

Semi-Pelagianism did not deny the doctrine of original sin as Pelagianism did, neither did it refute God’s grace as the only means of salvation for man, and yet it left room for the choice of man to cooperate in salvation thus affirming partial depravity of man, but not total depravity as the Bible asserts, “We love because He first loved us.” (1 John 4:19; ESV)

PELAGIANISM (AND SEMI-PELAGIANISM) IN OUR DAY

The Pelagian heresy (and semi-Pelagianism, too) can rear its ugly head in our day (and does).

Here’s how:

THE PELAGIAN CAPTIVITY OF THE CHURCH BY R. C. SPROUL

Shortly after the Reformation began, in the first few years after Martin Luther posted the Ninety-Five Theses on the church door at Wittenberg, he issued some short booklets on a variety of subjects. One of the most provocative was titled The Babylonian Captivity of the Church. In this book Luther was looking back to that period of Old Testament history when Jerusalem was destroyed by the invading armies of Babylon and the elite of the people were carried off into captivity. Luther in the sixteenth century took the image of the historic Babylonian captivity and reapplied it to his era and talked about the new Babylonian captivity of the Church. He was speaking of Rome as the modern Babylon that held the Gospel hostage with its rejection of the biblical understanding of justification. You can understand how fierce the controversy was, how polemical this title would be in that period by saying that the Church had not simply erred or strayed, but had fallen — that it’s actually now Babylonian; it is now in pagan captivity.

I’ve often wondered if Luther were alive today and came to our culture and looked, not at the liberal church community, but at evangelical churches, what would he have to say? Of course I can’t answer that question with any kind of definitive authority, but my guess is this: If Martin Luther lived today and picked up his pen to write, the book he would write in our time would be entitled The Pelagian Captivity of the Evangelical Church. Luther saw the doctrine of justification as fueled by a deeper theological problem. He writes about this extensively in The Bondage of the Will. When we look at the Reformation and we see the solas of the Reformation — sola Scriptura, sola fide, solus Christus, soli Deo gloria, sola gratia — Luther was convinced that the real issue of the Reformation was the issue of grace; and that underlying the doctrine of solo fide, justification by faith alone, was the prior commitment to sola gratia, the concept of justification by grace alone.

In the Fleming Revell edition of The Bondage of the Will, the translators, J. I. Packer and O. R. Johnston, included a somewhat provocative historical and theological introduction to the book itself. This is from the end of that introduction:

These things need to be pondered by Protestants today. With what right may we call ourselves children of the Reformation? Much modern Protestantism would be neither owned nor even recognised by the pioneer Reformers. The Bondage of the Will fairly sets before us what they believed about the salvation of lost mankind. In the light of it, we are forced to ask whether Protestant Christendom has not tragically sold its birthright between Luther’s day and our own. Has not Protestantism today become more Erasmian than Lutheran? Do we not too often try to minimise and gloss over doctrinal differences for the sake of inter-party peace? Are we innocent of the doctrinal indifferentism with which Luther charged Erasmus? Do we still believe that doctrine matters? Read more

(Pelagius via wikimedia. PD-US)

More reading: